In 1978, the French philosopher John Paul Sartre organized an Israeli-Palestinian conference titled “Peace Now?” The Israeli-Egyptian peace process was at its height and the conference brought together Israeli and Palestinian intellectuals from various backgrounds. Participating on the Palestinian side were, among others, Edward Said, who is considered one of the fathers of the post-colonial theory, the Palestinian historian Nafez Nazzal, the Israeli-Palestinian author, and member of the Mapam political party, Muhammed Wattad, who two years later joined Knesset as part of the party . Participating on the Israeli side were, among others, the historian Eli Ben Gal, the expert in Middle Eastern affairs Prof. Yehoshafat Harkaby, the philosopher Prof. Avishai Margalit, and Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz. The philosopher Benny Lévy , an Egyptian born Jew, and Sartre’s secretary, ran the conference. The conference protocols were published in edition 398 of Sartre’s academic journal, Les Temps Modernes in 1979. The quotations in this piece are taken from there. My deep thanks goes to Shaul Wachsstock who introduced me to this fascinating work and sent me the journal.

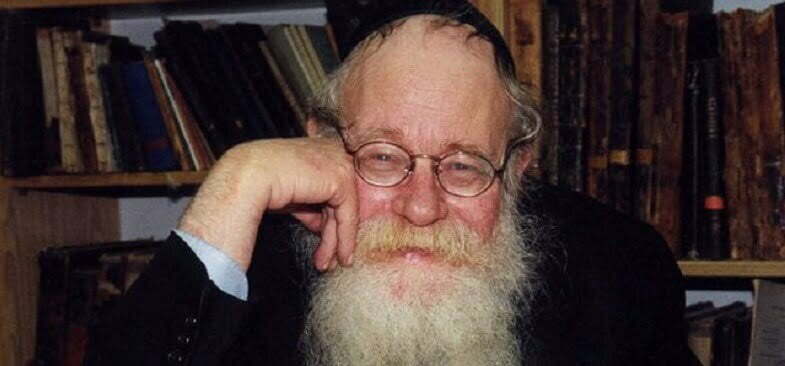

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz (1937-2020), born in Jerusalem, is primarily known throughout Israel and the Jewish world for his massive translation and explanation of the Talmuds. The protocols of the conference reveal another less-well known aspect of Rabbi Steinsaltz in terms of his attitude towards Jewish nationalism, the peace process, and the place of Israel in the Middle East. Due to lack of space, I will not relate to the rest of the speakers at the conference, nor Steinsaltz’s earlier or later positions on these subjects, but will focus on his statements at that particular conference.

Steinsaltz’s political position at the conference can be characterized as an anti-nationalist, but not anti-Zionist position. Steinsaltz opposed the definition of the Jews as only a nation or a religion, but described them as “a unit made up of diverse components” (pg. 481); a unit that is still currently solidified due to a shared history and the strength of separatism over the generations. On the other hand, he described nationalism as a danger or sin, and the state as simply a social tool or framework. When Prof. Margalit suggested limiting the State’s Judaism without limiting Judaism itself, and announced that his Zionism was dependent on the Law of Return which is an expression Jewish solidarity rather than nationalism, Steinsaltz fundamentally agreed. Over the course of the conference Steinsaltz similarly expressed a position of a limited Zionism, which sees the justification of a Jewish state in terms of an extended community, but does not give any special religious status to its existence as a political entity.

One can identify similar lines of thought between Steinsaltz’s position and the position of the Chabad stream of Hasidism to which he belonged. However, in contrast to Lubavitcher Rebbe’s well-known stance – in which he denounced returning any land for peace, Steinsaltz emphasized that he believed that all the occupied territories should be returned, including east Jerusalem and the Temple Mount. He even said that he was the first Israeli to express this position only a few days after the Six Day War, on his radio program “The Seventh Day.”

According to Steinsaltz, not only is the state not holy, but he compared nationalism to religious fundamentalism:

“This is the discovery I made after a while: nationalism is a religion that is no more honorable than any other religion. Even more so, it is often worse than religious fundamentalism, even [worse] than the [religious fundamentalism] of Khomeini, of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt […] Religious fundamentalism has at least one advantage over nationalism: by definition it establishes certain limits. Every religion has basic ideas that define the limits of behavior, emphasize what is permitted and not-permitted, creating limits that are upheld by conscience. Nationalism has no internal mechanism that establishes what is not-permitted. Nationalism is dangerous because it is absolute- limitless” (pg. 510)

In the Israeli context Steinsaltz considered Prime Minister Menachem Begin to be the archetype of the nationalist who is motivated, like most Israeli, by a feeling of existential fear. When one of the speakers suggested that Begin’s nationalism stemmed from religious feelings, Steinsaltz discounted the statement unequivocally and emphasized that Begin’s opinion was pure nationalism, even if he used religious terminology.

At the conference Steinsaltz expressed a more specific criticism of Israel’s cultural and geographic context. Firstly he characterized the chasm between communities in Israel as one of the central problems of Israeli society, even though the Palestinian issue allow Israelis to ignore it. He even joined Edward Said in criticizing the patronizing tone used by the Israeli speakers as they spoke for the Palestinians again and again. However, the height of his criticism came in a short description of the ideological sources of Zionism and his demand for a fundamental change in the relationship between Israelis and the surrounding Arab culture:

“Israel is a late product of the romantic movement which gave birth to European nationalism. Whether it wants to or not, it will need to become more and more middle eastern, in all sorts of ways, in order to create good relationships with its neighbors. In other words, Israelis must learn more about Arab culture, and get to know Arabic much better.

It’s possible that we have the opportunity to create a new relationship with the Arab world and Islam [than what is accepted in the West]. In the recent past, there were many Jewish communities that were somewhat integrated into the hegemonic Arab world. I do not think that this will happen again, since the circumstances of the 8th to 13th century no longer exist.

However, I believe that Israelis must strengthen their relationships with the Arab world, beyond scientific Orientalist academic studies in order to return to the circumstances that existed over a certain period of time in Jerusalem- during which most people knew how to communicate in Arabic and did not need a translator.” (pg. 508)

This quotation illustrates both Steinsaltz’s criticism of Zionism as a Euro-centric nationalist movement, as well as his suggestion for internal repair, which would be achieved through the middle easternization of Israeli society, and a better understanding of Arab culture. This was not a far off utopia in his eyes, but rather a return to the social and cultural status that existed in the Israeli-Palestinian context just a few decades before the establishment of the state. We can see in this position, which emphasizes the importance of direct and equal relationships between the cultures and nations, an echo of positions expressed by Israeli Spanish intellectuals at the turn of the twentieth century. It’s possible that these inadvertently influenced a young Steinsaltz, who was able to get to know Jerusalem as well as the various voices that arose from it during the Mandate period.