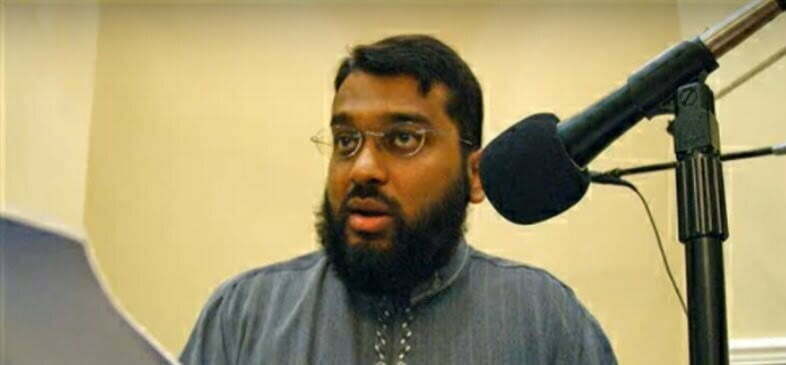

A few weeks ago, MEMRI – a popular website that tracks radical Islam around the world – addressed a sermon given by Sheikh Dr. Yasir Qadhi, a renowned Muslim cleric from Texas. The site accused Qadhi of defending “anti-Semitic comments” and of alleging that MEMRI misinterprets the way Muslim scholars around the world address the famous hadith from Sahih Muslim, the reliable collection in Sunni Islam, which reads:

The last hour would not come unless the Muslims will fight against the Jews and the Muslims would kill them until the Jews would hide themselves behind a stone or a tree and a stone or a tree would say: Muslim, or the servant of Allah, there is a Jew behind me; come and kill him; but the tree Gharqad would not say, for it is the tree of the Jews.

According to Qadhi, the hadith is not a prescription or a command, but rather a prophecy.

Although Yasir Qadhi was a devoted Salafist many years ago, he has changed his views dramatically and explicitly distanced himself from fundamentalism. For almost fifteen years, he has been considered one of the more pragmatic clerics in the US. Qadhi has condemned anti-Semitism and visited Auschwitz, and is even presented by MEMRI in a balanced light. Moreover, he is committed to adapting Sharia (Muslim law) to modern challenges, calls on followers to donate to social causes, and takes brave, innovative stands on complex issues such as Muslim apostates, tolerance of Muslim LGBTs and even American patriotism.

The current uproar began with a sermon Qadhi gave at the Epic Mosque in Texas as part of a series on the end of days in Islam. Qadhi discussed the final stage, in which creation will openly side with Muslims and Issa (Jesus) will kill al-Masih al-Dajal (the false Messiah). Some of the Dajal supporters who convert to Islam will be saved, but as for the rest (the Jews), the trees and the stones will attest that they are hiding behind them.

Qadhi could have ended the sermon on this messianic note. Instead, he boldly chose to address the problem with such hadiths, which make quoting from the tradition difficult and serve as a weapon for critics of Islam. To explain the contentious issue, Qadhi decided to take a deeper look at the hadith to determine whether it is indeed anti-Semitic.

Qadhi made three main points. First, he commented on the hypocrisy of criticizing such hadiths but not other ancient writings that convey racism or anti-Semitism. Second, he defined anti-Semitism as a European phenomenon that does not belong to Islam and noted that Muslims and Jews have much more in common than Jews and Christians, who were the ones to persecute Jews throughout the ages. Qadhi also recalled the flourishing of Jewish intellectual giants in Muslim countries, such as Iraq, Yemen and Morocco. He did not mention the limited status of “ahl a-dhimma” (“people of the pact”), but did note that the term “ahl al-kitab” (“people of the book”) did not have an anti-Semitic meaning.

His third argument, relating to the hadith itself, emphasized that killing Jews is a prophecy or a description of what will occur at the end of days, not a prescription. The hadith does not command any Muslim to kill Jews and according to Qadhi, no Muslim cleric draws his religious guidance from it. Why, he asks ironically, should those who do not believe in 88% of Islamic prophecies concerning the end of days choose to “believe” this one?

After the MEMRI reference, Qadhi shared a post on Facebook indicating he was hardly surprised, having already coped with accusations by US right-wing extremists who still consider him a dangerous preacher. A few years ago, for example, “proof” was published on an American website and on YouTube that Qadhi justified violence against Christians. This turned out to be the result of manipulative editing of fifteen lessons that Qadhi taught many years ago, in which he discussed the Islamic term “shirk” (idolatry or polytheism) and the hypothetical reality of an Islamic caliphate. In the clip, Qadhi is supposedly heard saying that Christians are “filthy”. What he actually said, in the full lesson, was that idolatry is filthy – much like the derogatory terms used for idolatry in Judaism (such as “abomination”).

Platforms like MEMRI are used to providing consumers with dichotomous ideas that lack complexity. To be sure, researchers for the website have tracked down quite a few authentic anti-Semitic Muslim statements. Yet it is a shame they do not extend fairer treatment to openly pragmatic clerics, who have explicitly distanced themselves from radical Islam and are even targeted by Muslim militants for doing so.

One does not have to accept Qadhi’s commentary on the famous hadith to appreciate his courageous engagement with this and other controversial issues. Not every rabbi or preacher who quotes an ancient verse from written or oral teachings is an “extremist” or an “anti-Semite” – especially if he has the track record to prove otherwise.

Elad Ben David is a PhD student at the Middle East Studies Department of Bar-Ilan University. His research deals with Islam in America, focusing on da’wa activity.

Translated by Michelle Bubis