Background

Hamas’ landslide victory in the 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council elections was a surprise not only for Israel, but also for the Palestinian Authority. President Mahmoud Abbas immediately appointed Ismail Haniyeh prime minister. However, his party, Fatah, refused to join Haniyeh’s government as long as Hamas continued to reject the terms laid out by the Middle East Quartet: recognizing Israel and the Oslo Accords, and ending the armed struggle.

Throughout 2006, Fatah and Hamas waged a bloody battle, chalking up hundreds of casualties. In May, Hamas Minister of the Interior Said Siyam formed a new security apparatus called the Executive Force, consisting of 5,000 operatives with SUVs and AK-47s. This was necessary, according to Siyam, as the existing security apparatuses (mostly Fatah-staffed) did not obey his orders. In January 2007, Mahmoud Abbas outlawed the new force. With that, half a year before taking over of the Gaza Strip, Hamas had ensured its independent security apparatus.

Back to May 2006. The same month Siyam formed his paramilitary force, five heads of Palestinian movements jailed in Israel’s Hadarim Prison signed the National Accord, also known as the Palestinian Prisoners’ Document. It was the first document ever to draw the boundaries of the Palestinian political consensus: an independent state along 1967 borders with Jerusalem as its capital, and the right of return for the refugees of 1948. The accord also called for armed struggle in the Occupied Territories and for integrating the Palestinian “resistance movements”, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, into the PLO – the Palestinians’ accepted umbrella movement since the 1960s. Official adoption of the document was cut short by the abduction of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit along the Gaza border in June 2006. Israel responded with harsh punitive action against Hamas, including the imprisonment of 33 Hamas MPs.

Despite fierce rivalry, including arrests and mutual assassinations, Hamas and Fatah agreed to form a unity government under Ismail Haniyeh in March 2007, after signing a reconciliation agreement in Mecca in February. Yet the joint government was short-lived: within three months, Hamas violently took over Gaza and expelled Fatah’s security forces in a series of attacks on government buildings, beginning on 10 June. Five days and 118 casualties later, the takeover of Gaza was complete.

Consolidation

Once it had banished Fatah from Gaza, Hamas focused on subduing the remaining opposition: the Dughmush and Hales clans and Salafi-jihadist groups. Its first victory came within a month, when Hamas forces freed BBC journalist Alan Johnston, who had been abducted in March by the jihadi group Army of Islam led by Mumtaz Dughmush. Haniyeh posed for a victorious photo with the freed reporter and Hamas spokesperson Fawzi Barhoum touted the release as evidence of the movement’s power: “There used to be 75,000 security personnel [in Gaza]. They failed to free Johnston, but Hamas succeeded.” At the press conference, Haniyeh expressed his hope that the captive soldier Gilad Shalit would be set free in a “dignified deal”, as Johnston was.

The clashes with the Dughmush clan and with the Army of Islam continued in 2008. In September, Hamas police raided Dughmush homes in the al-Sabra neighborhood in western Gaza in an attempt to arrest two family members wanted for killing a police officer. The confrontation resulted in 11 family members dead and 46 injured, and a police officer killed. In the raid, the police confiscated small arms, RPGs, grenades and other military equipment.

The same year, Abu Hafs, the leader of Army of the Nation – a Gazan group affiliated with al-Qaeda – appeared in a video in which he accused Hamas of not applying Sharia law in Gaza. Abu Hafs, who had been arrested several times by Hamas, claimed that the Army of the Nation was ideologically tied to al-Qaeda, but not organizationally.

This was the context for Sheikh Abdel Latif Moussa, the leader of the militant group Jund Ansar Allah, dramatically announcing the establishment of an Islamist emirate in the Gaza Strip, in a speech he gave at the Ibn Taymiyah mosque in Rafah. The group first garnered attention when its operatives tried to attack an IDF outpost at Karni Crossing in June that year. The attack failed and resulted in the death of three group members. Within the Gaza Strip, the group attacked internet cafes.

Hamas security forces surrounded Moussa’s mosque. In a seven-hour gunfight, 24 Palestinians were killed and more than 130 injured. Moussa himself killed a Hamas officer after he was captured at home, and then committed suicide with an explosive vest. The incident prompted jihadi elements in Gaza to accuse Hamas of “serving the interests of the Jewish usurpers of Palestine”.

Hamas’ ongoing offensive against local jihadists led to the abduction of Italian journalist and peace activist Vittorio Arrigoni in April 2011. The unknown group that captured him, the Brigade of the Gallant Companion of the Prophet Mohammad bin Muslima, demanded the release of all jihadi prisoners detained by Hamas, and especially Sheikh Hisham Saidani, a prominent global jihad militant. The group denigrated Italy for being an infidel country that continued to occupy Islamic lands.

After Arrigoni’s body was found on 14 April, Hamas issued a harsh condemnation and Prime Minister Haniyeh called the activist’s mother to convey his condolences. The home of the suspected captors in Nuseirat Refugee Camp was raided, resulting in two jihadists killed and four arrested, and five Hamas police officers killed. Following a request by Arrigoni’s family, the defendants’ death sentences were commuted to life imprisonment.

Sole rule: Ideology and practice

Hamas has two main reasons for wanting to eliminate rivals in Gaza: one ideological, the other pragmatic and related to party politics.

Ideologically, Hamas objects to the Salafi-jihadi view of the Middle East, and in fact the entire world, as an eternal battleground for the war between Islam and infidels. Salafist Islam often uses the term takfir to mark non-Muslims as infidels who are worthy of death unless they accept the dictates of Islam. Hamas, in contrast, has a primarily political agenda. Most Muslim clerics object to takfir, especially when it is used against other Muslims, and believe that God alone will judge humanity at the end of days.

Politically, Hamas believes in a Palestinian nation-state governed by the values of Islam, within British Mandate boundaries (“historical Palestine”). Salafi-jihadist groups contemptuously call these “the Sykes-Picot borders” and strive to erase them in favor of an Islamic caliphate.

In terms of faith, the Salafist movements advocate a puritanical version of Islam propounded by the medieval thinker Ibn-Taymiyyah. He was the most forceful representative of the Hanbali school, the harshest of Sunni traditions in Islam. Ibn Taymiyyah’s school adheres to imitating the lifestyle of the Prophet Muhammad as precisely as possible, and objects to artistic pursuits such as music and literature. Hamas, on the other hand, identifies ideologically with the Muslim Brotherhood and works to improve society through positive religious persuasion (da’wah), within the limits of current political circumstances.

Hamas made its criticism of Salafi jihad clear in a notice of death published after a Salafi suicide bomber killed Nidal Ja’afri, a member of Hamas’ military wing (the Izz a-Din al-Qassam Brigades) on the border with Egypt in August 2017. In the notice, Hamas called Salafi-jihadist views “a perverted ideology” (fakar munharef) and “a foreign implant” (dakhil). The notice portrayed Hamas as facing two adversaries: Israel externally, and Salafi jihad at home, with the latter trying “to shift the compass of holy jihad against the Zionist occupiers”.

Hamas’ Ministry of the Interior in Gaza, which controls the security forces, set up the Department for Political and Moral Guidance. As in many Middle Eastern militaries, the section was founded to instill state-sanctioned faith and steer the public in general, and security personnel in particular, away from religious fundamentalism. The department holds conferences, as well as visits to schools and even hospitals, where clerics affiliated with the establishment preach moderate Islam (wasati), as opposed to radical Salafist Islam.

For example, in April 2016, campus police at Palestine University in northern Gaza held a conference titled “Wasati Islam: A Way of Life”. Some 100 students attended. The event, published on the Ministry of Interior website, was aimed at “educating young men and women and university workers to steer clear of attempts at radicalization, and treating ideological perversion.” Colonel Zaki a-Sharif, deputy head of the department, gave a lecture on “fighting the radicalization and perversion that contradict our pure Islam and damage our security and society, the safety of residents, and the network of resistance.”

Another conference, for security forces, was held in April 2017 in the Central District headquarters of the Hamas police. The conference discussed the impact of radical ideology on society and how to address it. Colonel a-Sharif gave examples from daily life of teens radicalized through “the inversion of terminology and the arousal of emotion.”

Yet Hamas’ war on opposition in Gaza is also driven by a pragmatic goal: to enforce its political agenda on all factions, and to uphold the ceasefires reached with Israel after rounds of fighting over the last decade. In the years of ceasefire between rounds, Hamas became a de facto border police for Israel, preventing rocket fire across the border with a special police force formed for that purpose.

In April 2010, in a Friday sermon, Sheikh Abdallah a-Shami – a senior member of the Islamic Jihad – attacked the ceasefire agreement with Israel that was forced upon his movement after Operation Cast Lead. According to a-Shami, Hamas had done an about-face, going from criticizing the PA for calling its rocket system “useless” to calling the Islamic Jihad “traitorous” for firing rockets at Israel.

In a TV interview, a-Shami called Hamas “a party movement, first and foremost, that doesn’t accept others […]. It has to cooperate with others sometimes when they are important, but in terms of organizational structure and worldview, it does not accept the existence of others – whether they are Salafis, jihadis, or anyone else.”

The two movements are also fighting for control over Gaza’s mosques, which play a major role in shaping public opinion. According to a 2014 investigation by Ma’an News, Hamas controls almost 900 mosques in Gaza, while Islamic Jihad controls only about 100. The news agency documented some 86 instances in which rocket and RPG fire were exchanged in fighting over the mosques. Most of these clashes ended with Hamas forces arresting Islamic Jihad operatives.

Budget hike

Once Hamas established itself as sole ruler of Gaza, its budget skyrocketed: from an annual budget of about $40 million in 2005 (before Israel’s ‘disengagement’) to a whopping $540 million in 2010. According to Hamas MP Jamal Nassar, only $60 million came from taxes and the rest from “gifts and outside assistance” – most likely, euphemisms for income from smuggling and Iranian aid. Notably, Hamas’ budget is separate from the PA. In 2016, Hamas spent some $100 million – about 20% of its annual budget – on its military wing.

According to the Shin Bet (the Israel Security Agency), international organizations in Gaza have served as a conduit for funding Hamas. In June 2016, the agency arrested Mohammad El Halabi, the Gaza head of World Vision, one of the world’s largest Christian charities. His interrogation, stated Shin Bet, revealed that 60% of the organization’s annual budget had been diverted to Hamas through establishing humanitarian projects and fictitious agricultural associations. The agency also reported that aid money from the Turkish humanitarian group TIKA was similarly transferred to Hamas’ military wing.

Internal divisions

Every now and then, the media reports differences of opinion within Hamas. These are usually disagreements between internal and external elements (i.e., between leaders in Gaza and in exile), or between the military and political wings.

It is hard to tell how true these reports are. Hamas is highly secretive about its political decision-making. Its leaders and spokespersons seldom reveal strife within the movement, whether ideological or related to tactical-operational matters. Various interest-driven media fill the void with slanted reporting based on a predetermined agenda.

Nevertheless, disagreements do surface. The Arab Spring, which forced Hamas to quickly shift its regional allegiance from the Axis of Resistance (Iran-Syria) to the Islamist Axis (Egypt-Turkey), drove a wedge between members who favored loyalty to Assad’s Syria – despite the harsh images of harm to Sunni citizens – and those who supported cutting all ties with Damascus.

Mahmoud a-Zahar, a senior Hamas official, lambasted the decision of Khaled Meshaal, head of the political wing, to close Hamas’ offices in Damascus in early 2012. “Syria hosted the movement and the Palestinian resistance, but we betrayed it, injured it and stabbed it in the back”, he said, accusing Meshaal personally of “abandoning the principles and values the movement was founded on.”

According to a 2015 report by Al Arabiya, the Saudi network that opposes Hamas, Khaled Meshaal – who is identified with the global Muslim Brotherhood – was in favor of drawing away from Iran. In contrast, Muhammad Deif and the military wing of Hamas, which was generously supported by the Islamic republic, preferred to stay close to Iran in order to strengthen Hamas’ military capabilities. According to the article, the military wing is practically an independent organization and operates separately from the political wing.

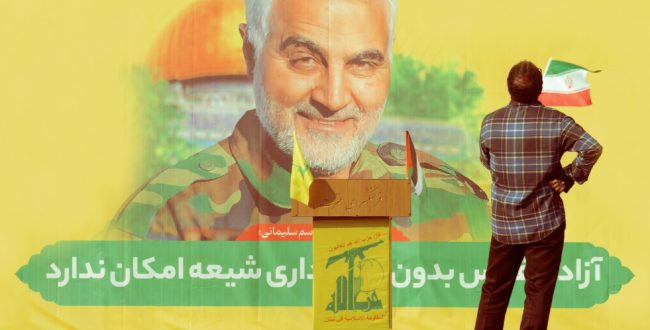

It seems, however, that Hamas has recently begun to revive ties with Iran. In 2016, Musa Abu Marzuq, deputy head of Hamas’ political bureau, praised Iran’s support of the movement; in 2018, Hamas senior official Husam Badran told me that relations with Iran were “back to where they were before we left Syria.”

Another topic of dissention is Israel. For several years, Hamas policy has been to boycott Israeli media (other than video propaganda aimed at Israelis, circulated by Hamas). However, several moderate political leaders, such as Hassan Yousef in the West Bank and Ghazi Hamad in Gaza, take a softer approach and talk openly with Israeli media. Hamad even published an op-ed in the Times of Israel in January 2015, criticizing Hamas’ failure to formulate a strategic political vision, including a stance on Israel. In October 2018, an Italian journalist’s interview with Hamas leader in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, was published in the popular Israeli daily Yediot Achronot – another indication of the changing attitude towards Israeli media among previous Hamas hardliners (although Sinwar denied approving the publication in Hebrew). A senior official in Hamas’ political bureau told me, off the record, that he believes the policy of boycotting Israeli media is wrong.

One explanation for this shift could be the leadership’s move from Qatar to Gaza in 2017, when Ismail Haniyeh replaced Khaled Meshaal with the head of the political bureau. Running the movement out of Gaza has greatly undercut the power of the leaders “in exile” and facilitated more dialogue between the military and political leadership.

Researchers Imad Alsoos and Nathan J. Brown have shown how Hamas responded to its economic and political crisis by electing a new Gaza leadership. The new heads, Yahya Sinwar and Saleh al-Arouri, are showing a surprisingly pragmatic approach to Fatah and Israel. Public pressure forced Hamas to ease up on former red lines, created an existential crisis, and threatened the movement’s continued rule over Gaza. “In 2017, [Hamas] showed that it could react not by accepting defeat passively but by turning crisis into opportunity”, wrote Alsoos and Brown.

Summary

Taking over Gaza in 2007 forced Hamas to complete its transformation from a religious opposition movement, whose main role was to criticize the Palestinian Authority, to an effective government in charge of 2 million people and hundreds of millions of dollars a year. This responsibility increased public criticism of Hamas for failing to propose a clear agenda on Israel. It also led to harsh self-reproach within the movement. Hamas is currently undergoing a fascinating process of learning and renewal, of which Israelis are barely aware.